I searched the websites of several nonprofits and failed to find any shots of people who use wheelchairs or crutches or walkers or canes. We are elusive creatures, but are we so hard to catch on camera? Doggedly persistent, I extended my search to magazines, periodicals, brochures, catalogs. The result? Not just few, none. Zero. Zilch. The organizations and businesses I targeted all promote the idea of diversity. In a country where the most recent census tallied 20% of the population as people with disabilities, why are so few of us pictured in promotional material?

We need representation, people. Much greater representation.

I decided to start with myself. At public events, I’m often the lone wheelchair user. At first, I felt self-conscious. People stared. Openly. Annoyingly. I used to get rattled by these marathon starers. I would look away or avert my eyes or move on as quickly as possible. “So give them something to stare at,” my wife, Leslie, suggested after I complained about a particularly antagonistic encounter. I upgraded my somewhat subtle purple chair to a day-glo orange. I revamped my arrogantly shabby wardrobe to something approaching urban chic. Now prepared, I told myself that I would welcome stares and gawking. I stopped dropping my glance. I looked back and said hello or remarked on the weather. In the exchange of glances and pleasantries, perhaps I could shift perception. Maybe even self-perception. When I looked at myself, what did I see? It was hard to answer that question. I thought photography might help.

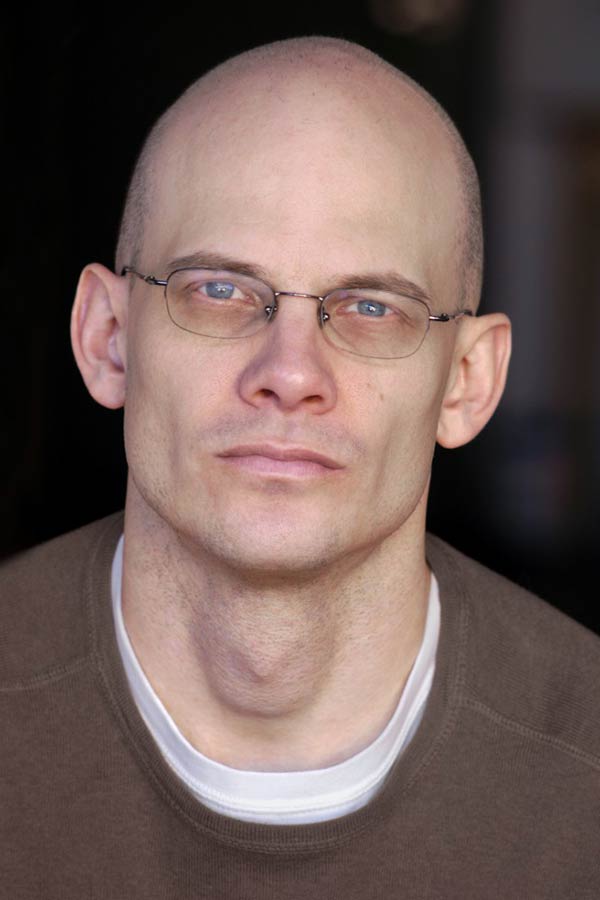

I found an incredibly talented photojournalist willing to work with a camera-shy guy transitioning to wheelchair use. It helped that he was (and is) a friend. It helped that he was (and is) disarming. It helped that he had (and has) tequila on hand. Looking in the mirror, I barely recognized my former athlete self. I wanted to reclaim that feeling of strength. Through David Binder’s lens, I saw myself united with my chair. I seemed sleeker and more centered. I felt my gravity and my confidence.

That’s why I entered a model contest for PhotoAbility, another first in a long line of firsts for me. The idea was brought to me by Scott Rains, whose Rolling Rains Report is a must-read on inclusive travel. PhotoAbility works to include people with disabilities in the travel, leisure, and life-style industries. Who knows where my image might be used, if at all, but at least I’m part of a pool of possibility.

Nonprofit leaders and businesses take note: if you promote diversity but ignore 20% of the population, your claims are hollow; your credibility questionable.Where do you find photos of people like me? Either hire a photographer and work with a local advocacy group or locate a clearinghouse of stock photos. PhotoAbility is a great place for you to start, too. Let’s take this journey together.

Less than one week home from the Intensive Care Unit, I’m ready for that close up now. Even in my pastel-colored hospital gown.

Great essay, Randy. Your words make me think of the comedian, Lilly Tomlin, “No matter how cynical you become, it’s never enough.”

A thoughtful essay. Reading it, I could hear your warm baritone voice and hear your concern.

Well said sir. As a practicing designer, it is always disappointing to see how little of the actual seen world is reflected back in commercially driven representation.

Sorry, don’t have budget for that.

We don’t want to seem too different.

We need to show people what they want to see.

Excuses. To me, it’s visual impoverishment.

Don’t people know their eyes and brains are hungry? Producing images that surprise and acknowledge human experience garner positive attention. It’s very easy to do.

By the way, have you considered racing stripes? You could get some badass detailing on your roadster. I’m partial to flaming skulls.

Honesty and directness is not easy because we so easily accept conformity and deflection. Randy, your honesty is a beacon!

Great article, Randy!! Can’t wait to read the other pieces you have written!

Yes. All so so true. This is likely of no use whatsoever, but the struggle is so much the same I had to mention it . . . I remember listening to a CBC Radio program several years ago about someone (can’t remember who, of course), black I think, lived in Southern Ontario I think, who worked very hard to get people of colour represented in advertising in Canada. And succeeded! He had to work closely with the advertisers of course, pushing pushing pushing, but eventually some kind of standard was developed and made law. And now, everywhere I turn I see the results.

I appreciate hearing about other successful campaigns, relevant irreverent quotations, and wacky style suggestions. Thanks for adding to the conversation.